Exploring British Country Music

In this article we explore the “Origins of Country Music” and the impact that the British have had on the very DNA of the genre.

For the past six years Jonny Brick has written album reviews, festival overviews in his Sightseeing series and topical essays on hot-button issues. He also started the UK Country Top 40 Chart, which ranks the best of British country music by their activity at any given moment.

The British Country Music Festival has commissioned Jonny for this four-part series.

The series “Exploring British Country Music” will be published every quarter until the 2023 festival.

- The origins of so-called hillbilly music (Part One).

- Into the twentieth century when American country music had commercial success in the live sphere and on record and could export worldwide (Part Two).

- Into the 2,000s and the rise in popularity of country music in the UK and our indigenous artists (Part Three).

- The here and now (Part Four), and trying to predict the genre’s future in Britain.

PART ONE: THE ORIGINS OF COUNTRY MUSIC

Introduction

In 2023, British country music fans will head en masse to the O2 Arena in Greenwich, or the OVO Hydro in Glasgow to enjoy acts who are making money for their record labels in America. Lady A, Thomas Rhett and Zac Brown Band are all signed to major deals where they have to make a return on their investment both on record and in the live sphere.

Stylists, vocal coaches, choreographers, guitar technicians, PAs, managers, booking agents and sound & light designers are all part of an artist’s retinue, with live music a key part of Britain’s entertainment sector. There is even a festival entirely dedicated to British Country Music!

But how did this music get to Britain in the first place? What forms has it taken in the decades since people first sung folk ballads without the means to reproduce them on a recording or even as sheet music? Why do people cram into venues big and small, sweaty and grandiose, to bellow along to songs about life, love, despair, hope and alcoholic consumption?

Maybe because this music was British, to begin with.

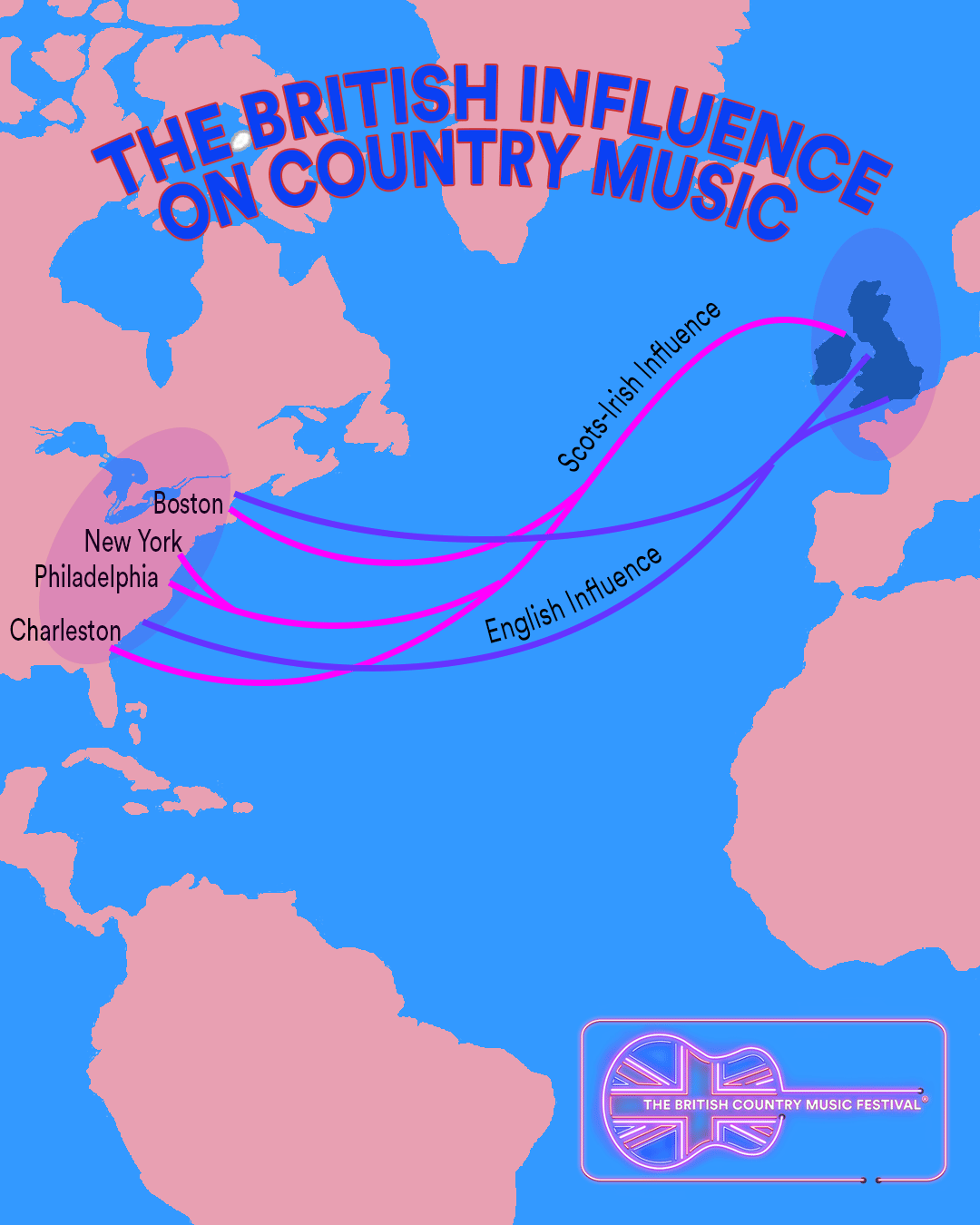

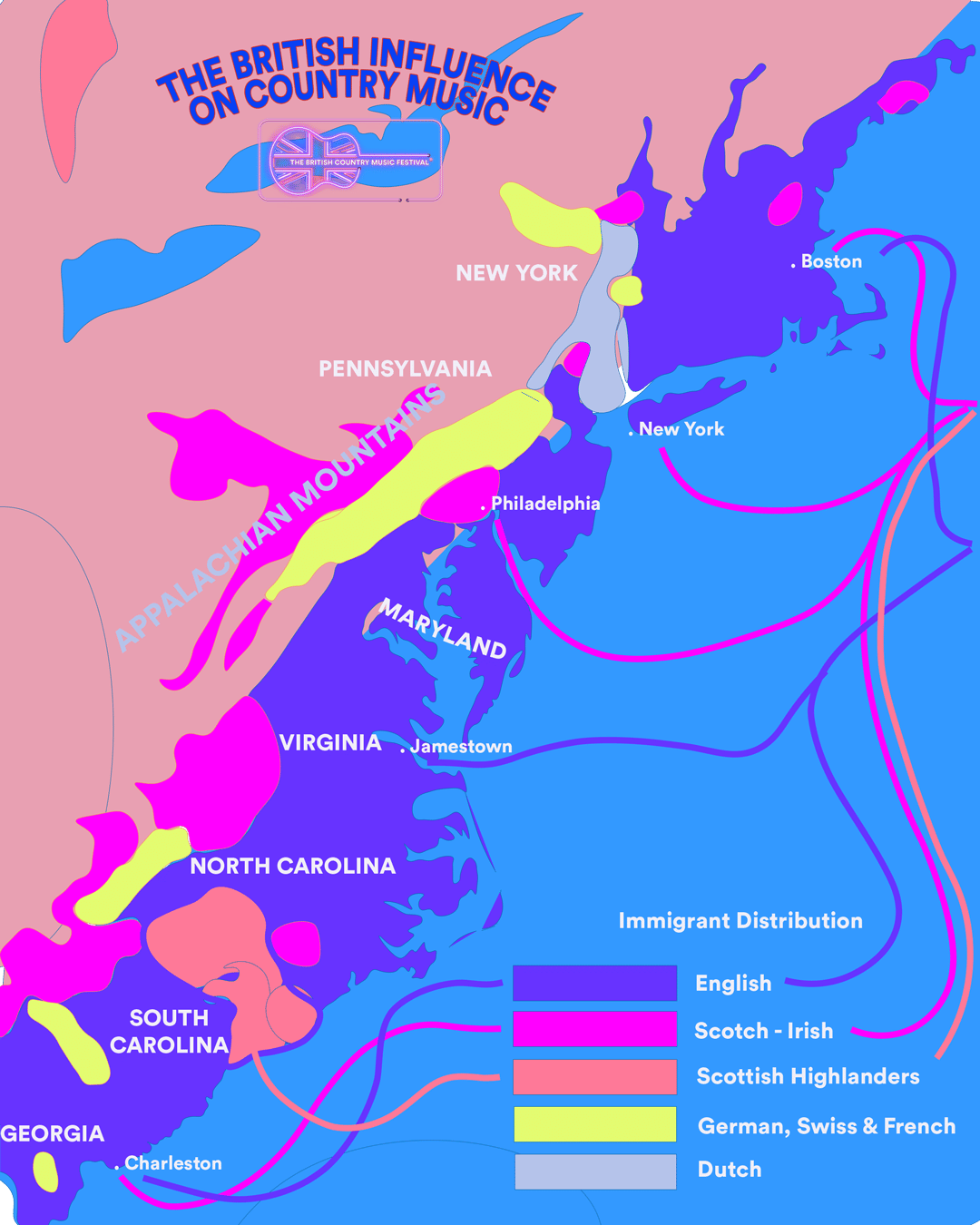

The origins of country music trace back to the pioneers from the British Isles who settled in the eastern American Appalachian mountain range. The genre, first known as Hillbilly music, emerged as a fusion of the ballads and folk songs of the English, fiddle and dance music of the Scots-Irish with the banjo and blues influence of African Americans. The documented origins and collection of early country music songs by folklorists such as Cecil Sharp, means much of what we know as traditional American music can be traced back to British roots.

The Scots-Irish People

- The origins of country music is rooted on the east coast

In the canonical book Country Music, USA by Bill C Malone, the story begins in the fertile crescent of hillbilly music between Texas and Virginia. The homesteaders carried on the ‘religious dissent’ brought over from England, Scotland and Ireland; there is a reason why the east coast still seems more British, and it’s because ‘the conservative and dissenting sects pushed into the back-country. These Methodists and Baptists brought their music inland too.

At the turn of the nineteenth century, evangelism spread the Word of God, but, Malone writes, there was also secular music with its “simple, singable melodies and song texts characterized by choruses, refrains and repetitive phrases.” Having renounced Catholicism, Calvinist Scots began to sing hymnal settings of the psalms in English. They were set to new tunes that were also brought West.

As life went on, stories from the Civil War era, gospel music, and popular songs sold as sheet music made their way into the canon. With no TV or radio, singing was as key a social activity as it was in a posh European salon, with accompaniment from a parlour organ, harmonica or autoharp.

Writing in 1943 as part of a book called The Great Smokies and the Blue Ridge, the folklorist John Jacob Niles contributed a chapter on Folk Ballads, which he had over three decades’ worth of experience in collecting (you can find many of his performances on Spotify). He refers to the ‘polite bribes’ given to his subjects in exchange for their songs, including whisky, tobacco, bacon, aspirin, soda and, in only two cases, actual money.

Niles first clears his throat: ‘There was a low point in the cultural life of the mountain people [who] were deceived by the glaze and the shine, the flitter and weak fineness of store-bought articles and the apparent advantages of citified music and dancing.

‘The ballad, once denounced as sinful,’ he writes, ‘was to be laughed down as silly’. This started in the 1870s when folk ‘were ashamed to appear in homemade clothes or to be caught singing “old-time music”. Plus, of course, those hymns ‘motivated by the most obvious and poorly harmonized tunes…confusing sentimentality with worship’. Singing was both ’emotional expression and recreation’ back in the day. Marvellously the counter to this was that women set up schools. They ‘believed in the simple homely virtues’, encouraged dancing and gave out prizes for singing and fiddling.

Interestingly, Bill C Malone notes, the Appalachian folk “could not easily accept the overt sexuality” of the British tunes, preferring sad, sombre tunes they had been handed down from them. This didn’t stop travelling musicians from learning the risqué tunes, but it must contribute to why heartbreak songs are still in demand from today’s audiences. The fiddle, as well as guitars and dulcimers, was seen as a tool of the Devil!

“Fiddling is an American tradition,” says Ray Benson of Asleep at the Wheel. “….and it goes back to our founding.”

“Fiddling is an American tradition,” says Ray Benson of Asleep at the Wheel. “I think it’s the most American tradition in music, and it goes back to our founding. They all brought their fiddles over because it was easier to carry a guitar and a fiddle than a piano and a brass band.”

Brian Peters was heading to Asheville, North Carolina, to teach at a summer school. In a piece for Living Tradition magazine in 2018, he commented on a BBC show called Wayfaring Stranger, presented by Scottish treasure Phil Cunningham and partially (two of three parts) available on YouTube. The show is very good at showing the Scottish and Irish links to country music, from shape-note singing to the present commercial era.

In 1736, there was an advert in a paper for a fiddle competition to celebrate St Andrew’s Day, with a new fiddle as a prize. This, Phil boasts, is thought to be the first mention of country music in print; it didn’t exist as a term beforehand! We see and hear Old Molly Hare, a fiddle tune that existed (and still exists) as The Fairy Dance in Scotland; then we see an academic dancing a jig with Phil watching on like a professor. He is also delighted to hold John Carson’s old fiddle, which was played on recordings in 1923, four years before Jimmie Rodgers became a superstar.

Before heading across the Atlantic Ocean, the Scots first headed to Northern Ireland, finding a new home in Derry/Londonderry (as it’s now known). Sometimes, Phil notes, “the songs were the only bit of home they had to hold on to”, and their identity was bound up as Ulster-Scots; at the smallest point, they are only 12 miles from coastline to coastline across the Irish Sea.

Ballad singers would sing their songs around villages and towns, offering the sheet music for sale to whoever was attracted to the tunes. Magnificently, the balladeer ‘the Good Man of Ballengeich’ who dressed in rags was, in fact, King James V of Scotland. He played the lute and was fond of inviting Europe’s top musicians to his court at Stirling Castle.

Peters was full of praise for Phil Cunningham’s adventure, ‘but where were the English?’ These were folk who shared traditions with those Scots with their ‘culture of independence, belligerence, strong family ties and fierce Protestantism’. The capital of North Carolina, after all, is Durham. One should never forget the North-Easterners who also carried folksong through the ages, passing them on orally without needing to write them in a songbook.

THE BRITS ARE COMING

- The first American census in 1790 listed 2,345,844 people of English origin, 188,589 Scottish origins, and 44,273 Irish origins. However, the portion of the population which was described as Irish was essentially Ulster-Scottish. The true Irishman never emigrated in any considerable numbers until they felt the pressure of the potato famine some fifty years later.

- The journey to America was difficult. First, migrants walked to an emigration port. Then they sailed for 6–10 weeks. The cost of a passage could be £3 – £9. However, many migrants became indentured servants and paid for their transportation by working for an agreed period after they arrived in America.

- One-third of the population of Pennsylvania was of Ulster-Scottish origin at the outbreak of the Revolutionary War. About half a million were transferred from Ulster to the Colonies between 1730 and 1770, which was more than half of the Presbyterian population of Ulster.

- Many Scottish immigrants headed for Virginia, the Carolinas, Georgia, and Kentucky. It has been estimated that about 385,000 people of Scottish ancestry lived in the Southern Colonies during the eighteenth century, while only about half of those Colonies identified themselves as English.

- Scots and Ulstermen fought in the Revolutionary War, and many contributed to the public life of the early days of the United States. Out of the twenty-two brigadier generals of George Washington, nine were of Scottish descent.

- When Washington first organized the United States Supreme Court, three of its four Associate Justices were related. One was a Scot, and two were Ulster Scots.

- Eleven of the fifty-six delegates who signed the Declaration of Independence were of Scottish descent. It was in response to an appeal from John Witherspoon that the Declaration was signed; it was preserved in the handwriting of an Ulster-Scot, secretary of congress.

- Musicologists and musicians have long recognized the Irish Scots’ musical influence on hymns, gospel, country and rock ’n’ roll music.

- Fiddles, folk songs and psalms of worship were carried by Ulster-Scots communities across the Atlantic.

- Distinctive forms of music developed in the regions where the Scotch-Irish settled – most famously in Appalachia and the South.

- The origins of Bluegrass music are a fusion of Scottish-Irish fiddle tunes, folk songs, and African-American banjo styles.

- Country stars like Patsy Cline (born Virginia Patterson) and Dolly Parton have Scotch-Irish ancestry.

Cecil Sharp

- The origins of country music are documented in English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians

This is where Cecil Sharp enters the story, along with trusty sidekick Maud Karpeles, whose contribution to country music is in danger of being as forgotten as a verse in an old folk song. In a 1917 book, English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians, Sharp celebrated his folk music sources as part of his “salvage folklore” field research. In fact, Sharp calls those hours “on the porch (i.e. verandah) of a log-cabin, talking and listening to songs were amongst the pleasantest I have ever spent”.

Sharp converted to folk music thanks to his love of country dancing. Having worked in Australia, he returned to his native London in 1892, and his folk song collection grew to over 4500 songs from “the exceedingly small class” of remote denizens of England. Plenty of his sources worked on farmland or the railways; some, but not all, were paupers.

Over in America in 1888, the American Folklore Society was started, along with those by state, including North Carolina and Kentucky in 1912. Harvard professor Francis James Child recorded over a thousand ballads in his catalogue in the late nineteenth century, setting up his own system of classification, which benefitted Sharp and Karpeles.

The pair went out West four times between 1916 and 1918, totalling a full year of research. Initially, Sharp advised on a production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in New York, then lectured on folk dancing. In his Living Tradition Magazine piece, Brian Peters also points out that Jane Gentry, a relative of the Hicks clan who lived in North Carolina, was an essential source for Sharp’s collection. The folk songs Sharp had been noting down in England had been assimilated from Scotland, certainly the lowlands, which bled into the northern English counties.

Cecil Sharp with trusty sidekick Maud Karpeles documented and collected early American folk songs.

“Our usual procedure,” writes Sharp, “was to stay at one or other of the Presbyterian missionary settlements” and then set out on foot to various settlements. The folk they found, in some cases, could not read or write but were “good talkers with elemental wisdom, abundant knowledge and intuitive understanding” gained from being “face to face with reality” and nature.

He and Karpeles headed to Tennessee and Kentucky first, with all the hardships of travel in the 1910s travelling on a (well-named) ‘jolt wagon’. The pair also headed to Virginia, to Charlottesville, where there was a university, and to Bath County, where there was a resort called Hot Springs. Asheville in Tennessee, meanwhile, had plenty of cars and electricity, so it was not precisely the backwoods. Appalachia was home to Cherokee natives and, in the early eighteenth century, Irishmen and northern English folk.

Karpeles took down the words while Sharp took down the tunes. In a preface to Sharp’s book, Karpeles writes that her subjects “maintain a sense of continuity…by strengthening, instead of destroying, their traditional culture”; she also expresses surprise that nobody asked about their project or was even curious.

Sharp’s focus is on the tunes rather than the performer, with folk music flourishing in its own niche without outside interference or commercial imperative. It was far away from the city, much as today folk music thrives in towns or less densely populated areas. Ironically, Cecil Sharp House is in Camden Town, not far from the Roundhouse and KOKO, which mainly play amplified music.

It boasts a lovely library as well as putting on gigs and workshops. A little pamphlet in the collection contains some of Sharp’s letters home. In it, he reveals that he is a vegetarian. He also reports that poor Karpeles’s luggage was lost or stolen en route.

Sharp was pleased that in the very first days of his visit, he met people who had manners that were “old-fashioned English”, using outdated vocabulary. While the Crown-owned every piece of English land, in Appalachia, the land belonged to the people whose ancestors handed it down to the next generation. The ‘servility’ of the English serf was absent in America, whose people were ‘freer’. Sharp soon realised that ‘bad economic conditions’ meant that this sort of atmosphere wasn’t universal across his research.

People were willing to sing to Sharp, often prompted by the collector himself. They echoed what Sharp was used to back in England, with the typical ‘straightforward, direct manner, without any conscious effort at the expression’. Interestingly, he notes, “no two singers ever sing the same song identically the same way”, thanks to that oral song transfer. Poetically, Sharp likens this to how flowers and animals mutate over time, “ultimately to the birth of new varieties and species”.

He does notice some differences: “I certainly never saw any one of them close the eyes when he sang nor assume that rigid, passive expression” of an Englishman. Back in Blighty, Englishmen seldom “separate the tune and the text”, with Appalachian folk more bardic in their delivery in a way that led to the hillbilly entertainers of the recorded era. Indeed, in Appalachia, Sharp writes: “I could get what I wanted from pretty nearly everyone I met, young and old”, rather than being limited to an older generation in England.

The music of his hosts was “uncorrupted but also uninfluenced by art music”. The tunes were pentatonic or ‘gapped scales’. Sharp is so overwhelmed he writes, “I cannot talk coherently about it yet”. He moans that he has to “fend for myself – make my own bed”, and he calls the hymns taught by the missionaries “literary garbage”. He also wants to teach them to read and write.

“It is wonderful that such old-world stuff should have emanated from America,” he concludes a letter written from Asheville in 1916. For her part, Karpeles notes that there was “no concert or even a community singing” and how “we never heard a poor tune”; naturally, she is appalled that “womenfolk ate after the menfolk had finished”.

An essay by John R Gold and George Revill, “Gathering the voices of the people? Cecil Sharp, cultural hybridity and the folk music of Appalachia”, notes that the collectors wanted to find “cultural continuity” between the Scots-Irish and the American peoples. His first impressions were that “there was little or no worthwhile American folk music’, but then he met other chroniclers of folk ballads and was hooked, going on a Frodo Bagginsesque quest to track down folksong in the Appalachians and beyond.

The essay’s authors note that the theories of people being “passive carriers of a traditional culture” are “imperialist and exploitative”, given that folk lived in rural areas away from the ways of the city. Instead, we should think of them as intuitive or worked at, which might remind someone of the difference between a gypsy jazz player, who might not be able to read music, and a member of a national orchestra who has undergone expensive training and time in a conservatoire.

American ballads dealt with soldiers and sailors, cowboys and paupers. British songs were somewhat romantic, although Gold and Revill call this separation “a new version of an old charade”. They also recall how enslaved Africans had to dress up as poor Englishmen to entertain ‘the culturally nostalgic ruling elite’ of Virginia.

The Great Scots-Irish Songbook

Sharp and Karpeles compiled over 250 folksongs ‘of English origin collected in the Appalachian Mountains’ across two volumes. There was also a 12-song best of entitled American–English Folk Songs. The introductory note warns readers not to forget that these are simple songs, ‘the product of unlettered, unskilled musicians…and must be judged upon their intrinsic merits.

‘Music, poetry…is good or bad, not because it is unsophisticated or ingenious, simple or complex, but because it is, or is not, the true, sincere, ideal expression of human feeling and imagination’. Above all, the ‘insistent human demand for self-expression’ is paramount in folksong.

There was something for every singer even among those 12 tunes which distilled the two volumes’ worth of songs. Their transcriptions are categorised as Songs, Ballads, Nursery Songs, Jigs and Play-Party Games. Among the 20 Play-Party Games were Up She Rises, Chase the Buffalo and Old Bald Eagle.

Get Up and Bar The Door was retitled Old John Jones, who tells his wife, Larry Grayson-style, to shut that door. Amusingly, they play a game of chicken, unable to break even when travellers come and drink their liquor and eat their food. When they want to kiss the woman of the house and John Jones resists, only then does his wife speak and orders him to shut the door having lost the game. What larks!

Ballads, Sharp had written, were narrative, romantic and ‘impersonal’, as if the singer is a mere vessel for the story. The lyric song is more personal, ‘a far more emotional and passionate utterance’. Side One Track One of the two-volume set, if we can refer to it as such, is The Elfin Knight, which has been recorded by Kate Rusby and has the refrain ‘blow winds, blow!’ as our narrator sets the protagonist (the knight) some impossible tasks. You can’t make a dress without needles or stitches, for instance.

A conversation between a child ‘going to meet my God’ and a knight forms False Knight Upon the Road, one of the 12 featured in that best-of set which English folk star Maddy Prior has arranged. Come All Ye Fair and Tender Ladies was performed in 2012 by The Chieftains and The Pistol Annies: ‘They’ll make you think they love you well then away they’ll go and court some other and leave you there in grief too well’.

Then come the murder ballads, which so influenced Nick Cave that he made a whole album of them. Hunt out his version of Young Hunting, entitled Henry Lee, a duet with PJ Harvey where ‘a little bird looked down’ on the victim’s corpse. The singer of Young Hunting comes to a sticky end, stabbed by his scorned woman who also meets an equally sticky end.

Edward, also known as My Son David, starts with a mother asking her son whose blood is on his sword. The Gosport Tragedy fed into Pretty Polly, a murder ballad which Dr Ralph Stanley has recorded, about a rich damsel courted by a man who knows that she is finer than any girl in New Orleans: ‘Her eyes are like charcoal, her hair is brown’.

The Cruel Brother has been recorded by folk acts Dick Gaughan, Archie Fisher and Lau. The title figure stabs his own sister who has been courted by a man who doesn’t ask his permission to wed her. Thus his sister’s bridal bequest includes a rope to hang him with. Lamkin, or Larkin as he has come to be known, is a stone mason who kills the wife and child of his client, a lord, who doesn’t pay him.

As in contemporary commercial country music, love is always in the air. The Wife Wrapt in Wether’s Skin was later recorded by Burl Ives as The Wee Cooper o’ Fife, the story of a barrel-maker marrying a ‘gentle’ woman of higher class. Those who don’t like nonsense folk syllables like ‘nickety-nockety-noo’ should avoid the Ives version but heed the lesson of listening to your husband. In the third decade of this century, we don’t look favourably upon the man’s idea to clothe his wife in sheepskin (‘wether’s skin’) so as not to hit his insolent lady without first hitting a buffer, thus technically not striking her own skin.

The False Young Man is a lament from a woman who effectively breaks up with a man who is ‘engaged with another true love’. It’s a lyric which was sung brilliantly and in harmony by Lady Maisery in 2012. The Dear Companion is another tender melody sung by a lady ‘left alone’ after being cheated on, while The Rejected Lover puts the shoe on the man’s foot after a lady scorns his offer to ‘shoe your feet…glove your hand…kiss your ruby lips’. He feels so awful that he wishes to have never been born, so as not to have ‘met her rosy cheeks nor heard her flattering tongue’.

The Suffolk Miracle is a warning to men not to chastise their children, using as an example the squire who wouldn’t let his daughter be with the man she loves. After he dies, he becomes the miracle, the ghostly apparition. Sally and Her Lover, or Lady Leroy also tells of a bold child who goes against the wishes of her father. The Sheffield Apprentice flees to London where he ‘steals’ a ring that a scolded lover plants on his person and is executed, seeking pity and sympathy from those who watch him hang.

Caroline of Edinboro Town also goes to London with her beau Henry, who must sail with the navy and leave poor Caroline pining at home. So upset is she that she ends her life. Edwin in the Lowlands Low returns from years at sea to his beloved Emma but is stabbed by her parents and thrown into the sea, sending poor Emma mad with grief. The narrator of Green Grows The Laurel also cries for a lost love, much as poor Texan musicians today deposit tears in their beer.

On the other hand, John of Hazelgreen is set up with a lady after she is found weeping by his father, while Waterloo (or Plains of Waterloo) has an enormously happy ending as it is revealed that the soldier is both the subject and the audient of the song! The Riddle Song, recorded by acts as varied as Doc Watson and Sam Cooke, is one of the playful tunes. Its lyric asks why a cherry has no stone and a chicken has no bone, with the answers ‘when it’s blooming’ and ‘when in the shell’. The hook is about love: ‘The story of how I love you it has no end.’

Many of the songs, as you can tell, are about familiar folktale figures, be they squires, knights or noblemen. Young Beichan is a prince who is captured and promises himself to his rescuer, who happens to be the daughter of the man who captures him. The Broomfield Hill, about a maiden who wins a bet to stay chaste after meeting her beloved at the top of the hill of the title, is a fun tune which has been tackled by Bellowhead and Ewan MacColl.

Even without detailing the stories, the titles evoke the early modern era in which they first became popular: The Simple Ploughboy, The Three Butchers and Will the Weaver. Also nestling in the collection is The Cherry-Tree Carol, a setting of Joseph the carpenter and his wife Mary which has been interpreted by Sting. The Messiah is present in both church and secular music.

Walking in the Same Direction

For the second episode of his series on the British roots of country music, Phil Cunningham’s voyage lands him in Appalachia, where the seeds of Music City and entertainers like Dolly, Hank, Merle and Jimmie Rodgers were sown. Ricky Scaggs and Jerry Douglas pop up to declaim their Scots-Irish ancestry: Ricky’s grandma was a Ferguson and dobro wizard Jerry is a great-grandson of a fiddler. After landing on the East coast, where everywhere was trees, they headed down the Wagon Road to Georgia, Kentucky, Tennessee and the Carolinas, carrying their instruments and singing their tunes. Land was cheap and plentiful.

‘We’re all walking in the same direction,’ Rosanne Cash says over a choir singing Poor Wayfaring Stranger; we all have a ‘deep desire to connect’ with those who came before us. Wayfaring Stranger is thought to be a Scottish ballad of the 1600s, based on the melody of The Dowie Dens of Yarrow. That murder ballad is sung by folklorist Rhiannon Giddens in the documentary, sharing the melody of the tune which Rhiannon herself famously sang on the TV show Nashville.

The Wayfaring Stranger

The Wayfaring Stranger is a 19th-century American folk song. The melody has been traced to Scotland, but the words have a point of origin in the American Civil War era. Though there are many versions, Emmylou Harris’s cover version is perhaps the best known

The Wayfaring Stranger is based on the melody of ‘The Dowie Dens o Yarrow’, a Scottish Border Ballad dating back to a collection of poems published in 1724. The Yarrow Valley stretches down through the Scottish borders towards Selkirk. As with many early ballads, the origins of ‘The Dowie Dens o’ Yarrow’ are mysterious.

In an oral tradition, it was common for ballads to have multiple versions. The stories told in song were subject to the local customs and experiences of those who sang them. Many different versions of this song exist today in both Scotland and the USA.

One of Cash’s most beloved recordings, this song appears on the album American III: Solitary Man. The lyrics perfectly capture the mortality that infused many of Johnny Cash’s later recordings.

The song’s lyrics do not mention religion, but they may be interpreted as spiritual. The singer describes himself as a wandering stranger and reflects on how transient life can be for all of us. It is easy to imagine Cash singing this song shortly before his death in 2003.

Rhiannon Giddens’s rendition of the song is a beautiful blend of bluegrass and Celtic sounds. Her angelic voice instantly draws you in, making you feel like she’s travelled through life’s ups and downs and feels relief at having come home to God.

Her choice to stay on one chord the entire song is haunting and angelic. Stunning bluegrass fretless bass playing.

Ed Sheeran’s performance of the traditional song ‘Wayfaring Stranger’ is built from loops in one take.

Traditional songs will change over time as they are passed on from performer to performer. Four different takes on one song illustrate how the DNA of a song is influenced over time.

There will be a trace of British influence in all country music. Ed Sheeran brings the tradition up to date using technology that would not have been available to the early settlers.

Walking in the Same Direction cont.

A lot of the Appalachian ballads had started off, oddly, as “printed broadsides” stuck up like a concert poster and written for money. Brian Peters believes that the popular ballads were examples: The House Carpenter (written way back in 1657!), Matty Groves, Barbara Allen and Lord Thomas & Fair Ellinor, are just a few.

Folk-Songs of the Southern United States is a very useful book by Josiah H Combs (no relation to Luke, as far as I know). He calls Cecil Sharp “the greatest authority” on folk music in England, quoting him as saying the culture in the Highlands of the South is ‘Anglo-Saxon’ rather than Celtic or Ulster or Scottish. Combs notes that words are changed across the years to remove place names, which is understandable as you don’t get ‘gypsies’ in the mountains. In the European song, he writes, the imagery of two shrubs denotes lovers united in death; in the folk song Lord Lovel, this becomes other plants. Turtle doves remain while weeping willows keep crying.

Jack Went A Sailin was originally about a British soldier in France whose wife finds him wounded in battle and nurses him back to health; this is transposed to Santa Fe, New Mexico. Bonnie James Campbell became Johnnie Campbell, a rider who ‘never home came’, and Mary Hamilton sets a child’s murder in the Mary Queen of Scots era, which has come down through the ages.

Little Sparrow is thought to derive from a Scottish ballad called Jamie Douglas, about an unhappy marriage that ‘fades away like morning dew’. The narrator ought to have ‘locked my heart in a case of gold and pinned it with a silver pin’. In the country song, the narrator wishes she could “fly so high” and stop her sobbing.

The Jolly Boatsman is a lovely lyric ballad where our protagonist wants to “have a little pleasure”. Nine months later, there comes a child and a cautionary moral: “Do not trust a young man one inch above your knee!”

The cruel song The Rich Old Lady is known in the USA as Johnny Sands or The Old Woman of London but, in Peggy Seeger’s treatment, ’round Tennessee’ did he ‘dwell’. She loved two men and wanted to cuckold her husband, making him blind and leading him to a river to drown him, as per his own wretched request. Yet he “stepped a little to one side”, and in she fell, meeting her end and amusing the listener with her tomfoolery.

Folk would socialise at parties, socials and shindigs or hoedowns, but ‘it is in the lonely, isolated cabin’ that folk music thrives. Combs himself follows in Sharp’s footsteps to visit a mountaineer and, bonding over a shared occupation; the stranger opens up to sing him some songs, having “laid his Bible aside”. This seems an apt metaphor for the origins of commercial country music, which will be covered at length in the second part of this essay.

Combs lists some songs of British origin, some with incredible numbers of verses. Fair Annie (“The Indians stole fair Annie as she walked by the sea/ But Lord Harry for her a ransom paid in gold and silver money”) goes on for 31 verses, with our heroine clasping her banjo and her two sons.

The Lass of Roch Royal is told in 27 verses. She is “not a witch nor a strumpet bold, nor a mermaid from the sea”. Her lover George capsizes when seized by an apparition of her: “his heart did burst” is how the saga ends. The Lass of Roch Royal gives some of its verses to the song Who’s Gonna Shoe Your Pretty Little Foot, which Woody Guthrie, the Everly Brothers and Richard Hawley have recorded.

The Rantin Laddie is a tale told by Maggie, a girl stuck at home with a child. The laddie is incensed in turn by a letter towards those who have “been so ill to my Maggie…so cruel to treat my lassie”—ditto Ranting Roving Lad, which has retained the Scots dialect words like ‘philabeg’ (kilt), ‘rokelay’ (cloak’) and ‘cockade’ (ribbons word in a hat). The first line is, “My love was born in Aberdeen, the bonniest lad that ever was seen”.

Staying in Scotland, The Banks of Sweet Dundee concerns Mary, who receives a fortune from her parents and goes under the wardship of her uncle, whose farmworker catches her eye. There are many deaths in the song’s verses, which must have made it fun to perform, and Mary lives happily ever after by the Dee. Turtle Dove was a ballad that informed the Robert Burns poem about a red, red rose. Today the tune is also known as The Blackest Crow.

Without any titles to copyright, song titles are elastic and unfixed. The murderer’s confession Rose Connelly became Down in the Willow Garden, the site of Rose’s murder. The Crafty Farmer (or Selling The Cow) is robbed by a bandit whose horse the enslaved person takes as a swap deal, with ‘five thousand pounds in silver and gold in a saddle bag which he’d swapped over. The American song ends with ‘you have put upon him a South Carolina bite’, which sounds to me like when someone boasts of being from Texas.

Lord Randal has been tackled on record by Steeleye Span, Martin Carthy, Ewan MacColl, Buffy Sainte-Marie and Burl Ives (him again). It also gave Bob Dylan an idea for the opening line and structure of A Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall, since it begins ‘where have you been, Lord Randal, my son?’ It takes the form of a chat between a father and his son, who is ‘sick at the heart’ from being poisoned and must bequeath his property to his family. This trope has fallen out of everyday use, although wills and testaments are still a crucial part of property transfer.

More cheerfully, There Was A Sea Captain includes a chorus of ‘fol dee die addy die ay!’ within its tale of the chap’s wife giving birth after being knocked up by a squire while he’s out at sea. The final verse warns men to ‘not blame your wife’ for a pregnancy out of wedlock. Perhaps the dramatic element of the song is the reason for its passage through the generations: the lady is called ‘thick round the waist’ by her husband and then cries ‘the colic!!’ as an excuse for her waters breaking.

Many other songs were familiar to Cecil Sharp from his collecting in England. The Maid Freed from the Gallows begins each of its mournful verses with a different addressee. The maid asks her dad, mum and partner if they can pay the hangman, whom she asks to ‘slack just a while so she can say goodbye to her loved ones. Fair Margaret & Sweet William is about a ghost who haunts her former beloved after she had perhaps died of a broken heart. June Tabor’s piano-led version is essential.

Christy Moore brought Black Is The Colour into the popular sphere, singing of a lady with “the sweetest smile and the gentlest hands”. Joan Baez turned the traditional Scots-Irish ballad, Jackie Munro, into Jackaroe, where our protagonist disguises herself as a soldier to steal away on the same ship as her beloved. The song concludes: ‘This couple, they got married, so why not you and me?”

In his book The Great Smokies and the Blue Ridge, John Jacob Niles gushes that the tunes of Scots-Irish descent are ‘couched in powerfully poetic verses and, historically, are part of our Anglo-American cultural inheritance’. He says that the most important ballad is the one noted by Harvard professor Francis James Child as Little Musgrave and Lady Barnard, known as Little Mattie Groves, whose “tune is as dramatic as a battle cry”. Child’s cataloguing, however, went heavy on epic rather than lyric, something that Sharp and Karpeles more than made up for.

Often Josiah Combs prefers the new American versions to the original Scots-Irish ones, giving Edward, one of those 12 in the best-of compilation, as an example. The ‘best-liked and most widely known’ ballad is Barbara Ellen, which is ‘more sentimental than dramatic’ and had such popularity that in one particular classroom Niles visited, every schoolchild knew it.

With the title Barbara Allen, a host of artists have recorded the song: Art Garfunkel, Frank Turner, Dolly Parton, The Everly Brothers, and Joan Baez have interpreted a folk standard, which begins with a pastoral setting and a man at his death. It is an incredibly lyrical song full of pathos and yearning, with ‘adieu, adieu to all my friends’ particularly wretched. No wonder it remained part of the canon in the era of commercial music-making.

Likewise, The Gypsy Laddie a popular song both north and south of the border. It was based on the true story of a gypsy charming, a high-born woman from Ayrshire and stealing her heart. Under the title Black Jack David, it was recorded by three prime folk musicians: The Carter Family, Woody Guthrie and Bob Dylan. Sun Records put out a version by the bequiffed rockabilly Warren Smith, becoming a warning to female listeners not to go off with ‘gypsy Davie’.

If one can compare folk and disco, To Cheer The Heart is very similar to Gloria Gaynor’s I Will Survive: ‘If he don’t care for me, I don’t care for him… Isn’t that a pity he is so full of his deceit’? The poor maiden’s new man ‘has plenty in his pocket but little in his heart, so she is full of despair. Come All Ye False Lovers, meanwhile, holds up a woman’s ‘John’ who is out on the sea. He returns and says: ‘Oh my dear jewel, I’ll never leave you again!’ They live happily ever after, true love conquering all.

St James’s Hospital, however, is about “a dear cowboy as cold as the clay”. By the 1910s, life in the new land has informed the sorts of songs that folk in Appalachia sing. Those songs were perfect for companies dealing in recorded music to sell back to audiences in the electric era of commercial country music.

And so, from its beginnings in Great Britain and Northern Ireland, country music followed its people across the Atlantic. Like all stories, it’s about people carrying traditions and lifestyles from one land mass to another.

Soon, Britain would get back country music with a bit of Southern twang and plenty of ‘ka-ching’!

Part Two will be published soon. Sign up for further notification

Further Reading

Further Reading for Part One The Origins of Country Music

English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians by Cecil Sharp

Folk-Songs of the Southern United States by Josiah H Combs

John Jacob Niles’ essay in The Great Smokies and the Blue Ridge, edited by Roderick Peattie

Jonny Brick is a songwriter based in Watford whose interest in country music was piqued in a Greenwich tourist shop in 2015. He went straight home and googled ‘Country Top 40’, discovering the best of Nashville and much more.

Jonny has attended every Country2Country festival since 2016 and has dived into British country music’s many festivals too. Having founded the Country Way of Life project in 2017, Jonny writes pieces at countrywol.com and presents the UK Country Top 40 Chart Countdown.

His four-part Story of British Country Music will examine the rise and rise of the genre since it ‘gave’ country music to America in the nineteenth century.